Fool's Gold: Exploring the History of April Fools' Day

- Theresa Wilson

- Apr 1, 2024

- 11 min read

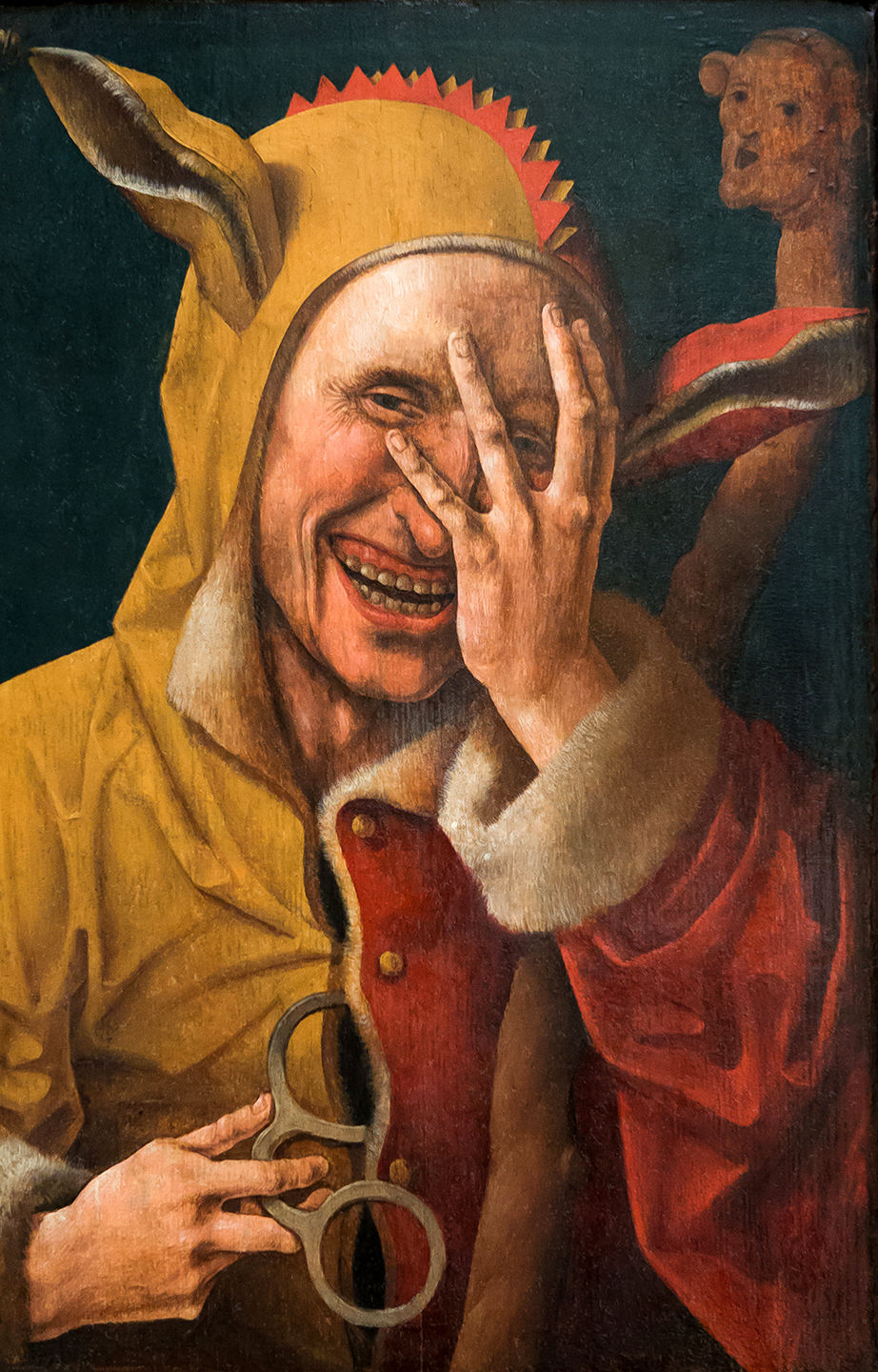

Welcome to our exploration of one of the most light-hearted and mischievous days of the year: April Fools' Day! Every April 1st, pranksters worldwide unite in a tradition of practical jokes and playful hoaxes, delighting in the art of trickery. From simple pranks among friends to elaborate media-driven spectacles, this day is marked by laughter, surprises, and the inevitable cry of "April Fools!" But where did this tradition originate, and why do we continue to embrace it? Join us as we delve into the rich history of April Fools' Day, uncovering its ancient roots and tracing its evolution through the ages. From its humble beginnings as a day for harmless jests among neighbors to its modern incarnation as a global phenomenon, we'll explore the enduring customs and timeless appeal of this beloved holiday. So buckle up and prepare to be entertained as we unravel the fascinating tapestry of April Fools' Day, where the only rule is to expect the unexpected!

Unraveling the Origins: Tracing the History of April Fools' Day

*While the exact origins of April Fools' Day remain shrouded in mystery, numerous theories have emerged to explain its intriguing beginnings.*

A debated connection between April 1st and foolishness traces back to Geoffrey Chaucer's "The Canterbury Tales" from 1392. In the "Nun's Priest's Tale," a vain rooster named Chauntecleer falls victim to a fox's cunning deception, with the fox referencing a nonsensical calendar date "Since March began thirty days and two," which would be 32 days since the start of March, ostensibly April 1st. However, the text further mentions the positioning of the sun in Taurus, a detail incongruent with April 1st. Scholars now propose a potential copying error in the manuscripts, suggesting that Chaucer originally wrote "Syn March was gon," which would imply 32 days after March, or May 2nd. This aligns with the historic significance of May 2nd, marking the anniversary of King Richard II of England's engagement to Anne of Bohemia in 1381.

The roots of April Fools' Day extend into the annals of history, with early mentions dating back to the 16th century. In 1508, French poet Eloy d'Amerval made reference to a "poisson d'avril" or "April's fish," possibly marking the first documentation of the celebration in France. Some historians speculate that the tradition emerged from the Middle Ages, where New Year's Day was observed on March 25th across much of Europe. In regions like France, where festivities extended until April 1st, those who adhered to the newer date of January 1st for New Year's mocked those still celebrating on the earlier date, giving rise to April Fools' Day. However, this theory faces challenges, notably from a 1561 poem by Flemish poet Eduard de Dene, featuring a nobleman playing pranks on his servant on April 1st, predating the official adoption of January 1st as New Year's Day in France. Moreover, April Fools' Day had already gained traction in Great Britain before the calendar year began on January 1st. These historical nuances add layers to the enigmatic origins of this beloved day of jests and hoaxes.

In the Netherlands, the origins of April Fools' Day often intertwine with the nation's history, particularly with the Dutch victory in the Capture of Brielle in 1572, where the Spanish Duke Alvarez de Toledo suffered defeat. A popular Dutch proverb, "Op 1 april verloor Alva zijn bril," translates to "On the first of April, Alva lost his glasses," with "bril" (glasses in Dutch) serving as a homonym for Brielle, the town where the event occurred. While this theory offers a localized explanation for the observance of April Fools' Day in the Netherlands, it fails to account for the international adoption of the tradition. In 1686, John Aubrey made the earliest British reference to the celebration, dubbing it "Fooles holy day." Then, on April 1st, 1698, a notable prank unfolded as several individuals were deceived into visiting the Tower of London under the false pretense of witnessing the washing of the lions.

April Fools' Around the World: Time-Honored Traditions and Pranks

Although countless April Fools' traditions exist globally, I'll be focusing on six specific ones that appear to be the most widely recognized and documented. While it's important to note that these traditions may vary in their current practice and prevalence, they offer intriguing insights into the diverse ways people celebrate this playful holiday. While I couldn't ascertain concrete evidence of their continued observance, these traditions are among the most extensively discussed and detailed ones available. If you're interested in exploring more, a quick search online will likely reveal a plethora of additional April Fools' customs from around the world.

Ireland

In Ireland, a traditional April Fools' Day prank involved entrusting the unsuspecting victim with what seemed to be an "important letter" destined for a specific recipient. However, upon opening the letter, the victim would find a message instructing them to "send the fool further." This playful hoax would often result in the recipient passing the letter along to another individual, continuing the chain of jests. While the origins of this particular tradition are unclear, it reflects the mischievous spirit of April Fools' Day and the delight in orchestrating harmless pranks. While this specific custom may not be as prevalent today, it serves as a reminder of the creative and amusing ways people have celebrated the holiday throughout history.

Italy, France, Belgium, and French-speaking areas

In Italy, France, Belgium, as well as in French-speaking regions of Switzerland and Canada, April 1st is celebrated with a tradition known as "April fish" (poisson d'avril in French, april vis in Dutch, or pesce d'aprile in Italian). This custom often involves attempting to affix a paper fish to the back of an unsuspecting individual without their notice. The imagery of fish is a prominent feature on many April Fools' Day postcards from the 19th to the early 20th century, symbolizing this playful tradition. Furthermore, newspapers often contribute to the festivities by spreading false stories on April Fish Day, with subtle references to fish serving as clues to the hoax. In France, boulangeries, patisseries, and chocolatiers participate in the celebration by prominently displaying chocolate fish in their shop windows. While this tradition continues to thrive in these regions, its origins trace back to a time when humor and lighthearted pranks were embraced as part of the April Fools' Day spirit.

Nordic Countries

In Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, and Sweden, April Fools' Day is celebrated with various traditions and is known as "aprilsnar" in Danish, "aprillipaiva" in Finnish, "aprilsnarr" in Norwegian, and "aprilskamt" in Swedish. One common practice across these countries is the publication of exactly one false story by most news media outlets on April 1st. In newspapers, this false story typically occupies a prominent place, often as a first-page article but not as the top headline. This tradition adds an element of surprise and amusement to the day, with readers eagerly searching for the fabricated news story amidst the usual headlines. While the exact origins of this tradition may vary across these Nordic countries, the spirit of playful deception remains a cherished aspect of April Fools' Day in the region.

Poland

In Poland, "prima April" or "First April" in Latin, has been a cherished tradition of pranks for centuries. On this day, elaborate hoaxes and pranks are orchestrated by individuals, media outlets, and even public institutions, often with a collaborative effort to lend credibility to the deception. The atmosphere is one of playful mischief, with serious activities typically avoided, as every statement uttered on April 1st could potentially be false. Such is the strength of this conviction that historical events have been backdated to avoid association with April Fools' Day, as evidenced by the Polish anti-Turkish alliance with Leopold I, which was signed on April 1st, 1683, but backdated to March 31st. Interestingly, in Poland, some consider April Fools' Day festivities to conclude at noon, after which any further pranks are deemed inappropriate or lacking in refinement. This nuanced approach to the timing of April Fools' Day reflects the cultural significance and evolving customs surrounding this playful tradition in Poland.

United Kingdom

On April Fools' Day in 1980, the BBC made headlines with a prank announcement that Big Ben's iconic clock face was going digital, even offering the clock hands as a prize to the first person to respond. This playful deception is a classic example of the April Fools' Day spirit, where unsuspecting individuals become the "April Fool" upon realizing they've been tricked, often signaled by the exclamation "April Fool!" In the UK, as well as in countries influenced by its traditions, such as the United States and Canada, the custom of shouting "April Fool!" to reveal a prank remains prevalent, a tradition documented by folklorists Iona and Peter Opie in the 1950s. However, there's a notable twist to this custom—the tradition typically ceases at noon, after which playing pranks is considered taboo, and the prankster themselves becomes the "April Fool." In Scotland, April Fools' Day has its own unique name: "Huntigowk Day," derived from "hunt the gowk," with "gowk" meaning a cuckoo or a foolish person in Scots. Traditional pranks on this day involve sending someone on a wild goose chase with a sealed message supposedly requesting assistance, only for the recipient to discover a humorous message inside, such as "Dinna laugh, dinna smile. Hunt the gowk another mile." Interestingly, in England, a "fool" is known by various regional names, such as "noodle," "gob," "gobby," or "noddy," reflecting the diverse linguistic landscape of the country. These regional variations add further color to the tapestry of April Fools' Day customs across the UK and beyond.

Pranks Around the World: April Fools' Day and Comparable Traditions

April Fools' pranks have a long history of amusing and sometimes bewildering unsuspecting participants. In Boston's Public Garden, one memorable prank warned visitors against photographing sculptures, claiming that the light emitted would somehow erode the artworks—an inventive twist on the classic prank formula. Another ubiquitous joke involves replacing the creamy filling of an Oreo cookie with toothpaste, resulting in an unexpected and unpleasant surprise for the unsuspecting snacker. Similar pranks involve substituting familiar objects, particularly food items, with unexpected alternatives, such as swapping sugar for salt or vanilla frosting for sour cream. Beyond individual pranks among friends and family, April Fools' Day has also seen elaborate hoaxes orchestrated by media outlets, corporations, and even government entities. In a now-legendary example from 1957, the BBC aired a segment on their Panorama current affairs program claiming to depict Swiss farmers harvesting spaghetti from trees—a hoax that prompted numerous inquiries from viewers eager to purchase their own spaghetti plants. The BBC was forced to admit the ruse the following day, illustrating the power of April Fools' pranks to captivate and confound audiences. In today's digital age, April Fools' pranks have taken on a new dimension, with the internet providing a platform for global dissemination of hoaxes and the potential to embarrass a wider audience than ever before. With readily available global news services, even the most outlandish pranks can quickly spread and catch unsuspecting individuals off guard, underscoring the enduring appeal and creativity of April Fools' Day mischief.

On December 28th, Spain and Hispanic America observe the equivalent of April Fools' Day, coinciding with the Christian celebration known as the Day of the Holy Innocents. While the Christian holiday is primarily a religious observance, the tradition of playing pranks on this day has become an annual custom. In Hispanic America, after executing a prank, it's common to exclaim, "Inocente palomita que te dejaste engañar" (meaning "You innocent little dove that let yourself be fooled!"). In Argentina, pranksters may jest, "¡Que la inocencia te valga!" translating to advice not to be as gullible as the victim. In Spain, a simple "Inocente!" suffices, while in Colombia, the phrase "Pasala por Inocentes" is used, indicating that on this day, one should let things slide as it's the Day of the Innocent. In Belgium, December 28th is recognized as the "Day of the Innocent Children" or "Day of the Stupid Children," where historically, parents, grandparents, and teachers would play tricks on children. However, the celebration of this day has waned in favor of April Fools' Day. Yet, on the Spanish island of Menorca, "Dia d'enganyar" or "Fooling Day" is observed on April 1st, owing to the island's history as a British possession in the 18th century. Similarly, in Brazil, April 1st is known as "Dia da mentira" or "Day of the Lie," influenced by Portuguese traditions. This convergence of cultural influences has led to diverse expressions of playful deception across different regions and countries, enriching the tapestry of global prank traditions.

In many English-speaking countries, including Britain, Ireland, Australia, New Zealand, and South Africa, there's a playful custom observed mainly by children on the first day of the month. It involves saying "pinch and a punch for the first of the month" or a similar variation. The recipient of this playful gesture might respond with "a flick and a kick for being so quick," to which the initiator might retort with "a punch in the eye for being so sly." This exchange is lighthearted and often done in good fun among friends or family members. Additionally, in Britain and North America, there's a lesser-known tradition of saying "rabbit rabbit" upon waking on the first day of the month, believed to bring good luck for the rest of the month. This custom, although less widespread, adds to the array of unique superstitions and rituals observed in different cultures around the world.

Reactions and Responses: The Reception of April Fools' Day

Navigating the realm of April Fools' Day pranks and hoaxes sparks a range of opinions, illustrating a polarizing divide among critics. This dichotomy is exemplified by the reception to the infamous 1957 BBC "spaghetti-tree hoax," which left newspapers divided, some lauding it as a great joke while others condemned it as a deceitful manipulation of the public's trust.

Advocates of April Fools' Day argue that the tradition fosters humor, camaraderie, and belly laughs, which contribute positively to mental and emotional well-being. They highlight the stress-relieving and heart-health benefits of laughter, viewing April Fools' as a light-hearted outlet for creativity and amusement. Numerous "best of" April Fools' Day lists showcase exemplary pranks, campaigns, and innovations, praising their ingenuity, writing, and overall effort. Conversely, detractors criticize April Fools' hoaxes as manipulative, rude, and potentially harmful. They argue that such pranks promote Schadenfreude and deceit, often at the expense of others' feelings or well-being. There's a concern that genuine news or important warnings issued on April Fools' Day may be dismissed as jokes, leading to confusion, misinformation, and even legal or commercial consequences. This risk is heightened in the age of social media, where misinformation can spread rapidly. In recent years, amidst global crises such as the Covid-19 pandemic, some organizations and individuals have opted to cancel April Fools' Day celebrations out of respect for the seriousness of the situation. In Thailand, authorities issued warnings against sharing fake news online, highlighting the potential legal repercussions, including imprisonment. Ultimately, the debate surrounding April Fools' Day reflects broader discussions about humor, ethics, and the responsible use of media and communication. While some revel in the light-hearted mischief of the day, others caution against its potential negative impacts, underscoring the need for thoughtful consideration and sensitivity in navigating April Fools' Day and its traditions.

When Truth is Stranger Than Fiction: Real News Mistaken for Hoaxes

April 1, 1946: Warnings about the Aleutian Island earthquake's tsunami that killed 165 people in Hawaii and Alaska.

April 1, 1984: News that the singer Marvin Gaye was shot and killed the day before his 45th birthday by his father Marvin Gay Sr. on April 1 1984. Several people close to Gaye such as fellow singers Smokey Robinson and Jermaine Jackson didn't believe the news initially and had to call other people who knew Gaye to confirm the news.

April 1, 1995: News that the singer Selena was shot and killed by the former president of her fan club Yolanda Saldivar on March 31, 1995. When radio station KEDA broke the news on March 31, 1995, many people accused the staff of lying because the next day was April Fools' Day.

April 1, 2005: News that the comedian Mitch Hedberg had died on March 29, 2005.

While the above instances are not exhaustive, they are among the most notable cases of real news being mistaken for hoaxes. If you're eager to explore more examples of genuine news stories that were initially thought to be pranks, a simple Google search will provide you with a wealth of additional information.

In conclusion, delving into the rich tapestry of April Fools' Day reveals a fascinating blend of history, tradition, and human ingenuity. From ancient customs to modern-day pranks, this playful holiday continues to captivate and entertain people around the world. Whether it's the timeless allure of a well-executed joke or the creative innovations of elaborate hoaxes, April Fools' Day remains a cherished celebration of laughter, camaraderie, and the joy of a good-natured trick. As we bid adieu to our exploration of its history, let's carry forward the spirit of whimsy and merriment, embracing the lightheartedness that April Fools' Day brings to our lives each year.

The photos used in this blog post are sourced from Google and do not belong to me.

.png)

Comments